Change management is an essential part of IT service management (ITSM), and it's a tightrope walk between implementing the change as fast as possible and mitigating the risks. The risks go up when it's an emergency update. According to Harvard Business Review, 70% of change initiatives fail.

But emergency changes are important, they’re essential to keep the business flowing and to mitigate losses. Let's explore the emergency change control process and five best practices for it.

Change in ITIL

Change management is a process used to ensure that a change within the IT infrastructure is handled with the least disruption to IT services and the least impact on the business processes. From an ITIL perspective, change can be anything from migrating to a different service desk solution or a shift from on-premise infrastructure to cloud.

There are different change categories with different steps, starting with submission, where change requests are made and tickets are created, and ending with closure, where the change is marked as successful, failed, or incomplete. After submission is the planning stage, where the expected time, service disruptions, etc. are calculated and conveyed to the stakeholders. The plan is further approved by the change advisory board in the next stage, following which the change is implemented. After this comes the review stage where any issues that arose during implementation are fixed out, following which comes the closure stage.

Since ITIL 4, change management became change enablement. The name change signified how the responsibility for the change was shared among all the employees of the organization and how instead of managing the change, employees were empowered to make the change themselves.

When does a change become an emergency change?

According to ITIL, there are mainly three types of change: standard change, normal change, and emergency change.

Standard change is a common change or a change that happens frequently and routinely. There isn’t anything special or specific about them and they usually follow a set of repeatable steps, and because they are routine, they require minimal planning.

Standard changes are easy to predict and hence can be automated to a large extent. They rarely present issues and the risks associated with them are calculated way before the routine steps are designed. Routine hardware updates, software patches, etc are treated as standard changes.

Normal changes lie in between standard changes and emergency changes. They’re not routine like a standard change and require careful planning and approval before implementation.

A normal change presents unknown risks and cannot be carried out with repeatable steps like a standard change; they usually need a unique plan and implementation. Depending on the risk and impact, normal changes are further classified into major(high risk, high impact) and minor(low risk, low impact).

A change is considered to be an emergency change when it has to be made as soon as possible. When delays to the change can be extremely costly to the organization or can create a sustained service disruption. This could be a security patch against a huge security vulnerability revealed recently or managing a server outage.

Since time is of the essence, compromises are made on testing and the approval process in exchange for faster implementation, and often a higher level of risk is accepted.

While they’re rarely predictable, they’re crucial for continual service delivery and the organization and its ITSM needs to be prepared for emergency changes for a consistent user experience.

What does ITIL recommend for handling emergency changes?

According to ITIL, the process for emergency change should begin just like any other change - by creating a request for change. The change manager will bring this to the attention of the ECAB or Emergency Change Advisory Board. This will be composed of members of the Change Advisory Board who are available and have the expertise and authority to make decisions regarding the change.

The ECAB members are responsible for weighing the risks of implementing the proposed change as an emergency change and the risks of delaying the change and implementing it as a normal one. In some cases, if the risks outweigh the benefits, the ECAB may decide to proceed with the change as a normal one.

If ECAB approves the change, the change owner will plan and design the change. They’re also responsible for building and testing the change if required. Once tested, the change owner will coordinate the implementation of the change. The configuration management database is updated to reflect the changes during the implementation phase.

Once implemented, the change owner will review to mark it as a success or a failure.

If failed, the change owner will initiate the back-out process. Back-out is an element that is rather unique to emergency changes. It is used to bring the systems back to the initial state if the change fails, or if the change presents new risks or issues.

In practice, this means that the emergency change is handled like an accelerated version of a normal change. Since it won’t be expected or routine, you’ll need unique approaches to tackle the change. But because of the time constraint, the approval and testing will be limited. And often a higher level of risk will be accepted by the ECAB, as the delays may prove costly.

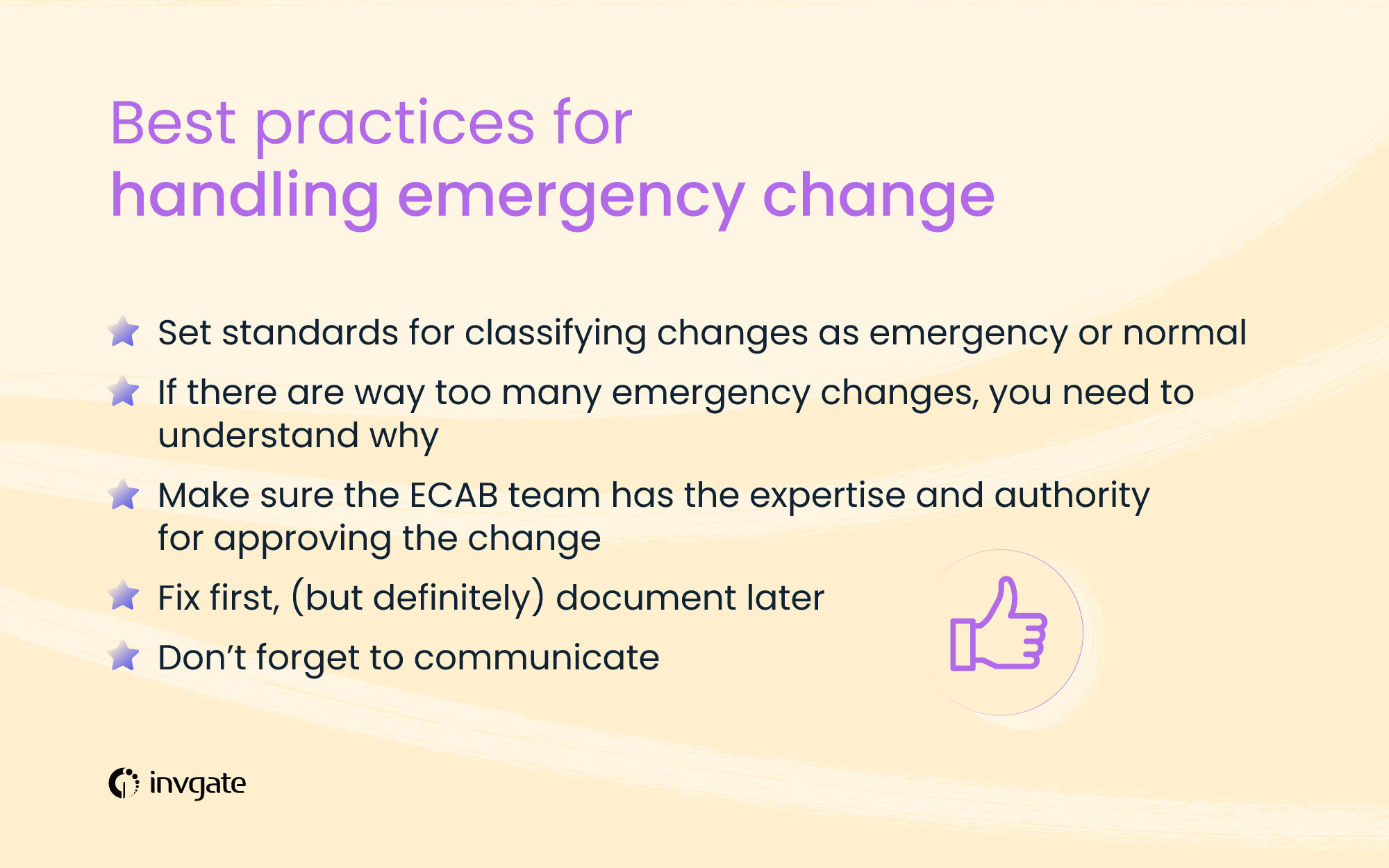

Best practices for handling emergency change

Set standards for classifying changes as emergency or normal

One of the most discussed points about change management is deciding if a change is to be treated as a normal one or an emergency. It's easy to classify the extremes of both, for example, it's easy to classify mitigating a cyberattack as an emergency change, and it's easy to treat a feature update as a normal change.

But boundaries often get blurred, let’s say when a feature update is blocking key business processes. And the organizational environment can make change requesters to treat all of their changes as emergencies. For example, if the change advisory board convenes only every two months or so, people may not way to wait that long to get their change approved, making them submit every change request as an emergency.

Emergency changes present high risks to the organization as the priority is on speed. So its important to set standards to classify changes as emergency or normal changes.

If there are way too many emergency changes, you need to understand why

As mentioned above, too many emergency changes can add unnecessary risks to the organization. And at some point, these risks can outweigh the benefits. Therefore you have to keep monitoring the overall picture when it comes to changes across the organization.

Analyze the number of normal, standard, and emergency changes, how many of them were successful, how many emergency changes were in fact actually emergencies, and if the risks were actually worth it. This should help you understand if you have way too many emergency changes approved in your organization.

If you do, try to understand why. Maybe it's an organization’s culture that encourages high-risk behavior in exchange for speed. Or it could be a passing trend; maybe the organization is fending off a series of targeted cyber-attacks.

Either way, focus on reducing emergency changes in the long run. This will be a fine balance; inculcate a culture of treating all changes as normal and you may face significant costs as services go down for long durations.

Make sure the ECAB team has the expertise and authority for approving the change

It’s relatively easy to build a CAB with members having the relevant expertise and authority for the change, but it requires a bit more effort for ECAB. When speed is important, it may not be easy to get all the members of CAB to discuss and approve the change - hence the ECAB. But this does not mean people without the expertise should make the decision.

It may be a good idea to form a clear picture of the chain of command and field of expertise among the CAB so that everyone knows who is absolutely necessary to form the ECAB for the specific emergency. For example, in the case of isolating a network to mitigate a cyberattack, network engineers may be important.

And at the same time, it would be prudent to not rely on one single person for expertise on a subject. Emergency changes should not be delayed just because of the absence of one person.

Fix first, (but definitely) document later

When delays in change can be costly, you’ll need to come up with quick solutions and deploy them in the shortest possible time. And while documenting the changes and their impact is important, the priority should be on implementing the change. Focus on designing the solution and planning how it will be rolled out.

But once implemented, the change and the affected components must be tracked and documented, both for further support and for clarity among the IT support team.

Don’t forget to communicate

When changes are rolled out rapidly, communication often takes a backseat, and this is reasonable. When a plane is on a downward spiral, the first job of the pilots is not to announce to the passengers that the engines are on fire or that there’s smoke in the cabin.

But once the changes are implemented and the smoke clears up, it's important to let the stakeholders, the employees, and the users know what necessitated the change, what was changed, and how it will affect them. To use the aviation analogy again, it may be a good idea to keep the ANC acronym - Aviate, Navigate, Communicate in your mind. Get your aircraft flying again, point it in the right direction, and communicate with the affected players.

|

|

"Your approach to managing the change shouldn't be drastically different than your typical change management process. The major difference is how quickly communication of a change needs to take place. Ema Roloff |

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the different types of change according to ITIL?

The three types of changes are normal, standard, and emergency changes. Standard changes are carried out often, they’re predictable and often follow a set of repeatable steps. Normal changes are planned changes, but require a specific and unique approach, and are not routine. Emergency changes are similar to normal changes but are in response to something that requires immediate attention, such as security issues. They’re often executed on a shorter timeframe compared to other changes.

When does a change becomes an emergency change?

When a change has to be executed in a short time frame, when delays can be costly to the business, the change becomes an emergency change. They’re necessary to ensure service continuity and uninterrupted service delivery.

.jpg?upsize=true&upscale=true&width=780&height=205&name=how-to-create-a-service-level-agreement%20(1).jpg)